Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Welcome to Flightinfo.com

- Register now and join the discussion

- Friendliest aviation Ccmmunity on the web

- Modern site for PC's, Phones, Tablets - no 3rd party apps required

- Ask questions, help others, promote aviation

- Share the passion for aviation

- Invite everyone to Flightinfo.com and let's have fun

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Thunderstorm movement

- Thread starter flyboyzz1

- Start date

Way2Broke

Member

- Joined

- Feb 24, 2005

- Posts

- 2,882

kansas

Seeee yaaaaaaaaa!

- Joined

- Mar 28, 2006

- Posts

- 125

The anvil typically shows the direction of movement. The anvil shaped top is formed by the upper level winds shearing off the top of the storm. The way I understand it, is that these winds are what limit the vertical development of the storm.

Agreed. That's what I found during weather mod, anyway.

Upper winds don't shear off a convective cell. The cell is formed by differential temperature. The vertical progression of the cell is stopped by either an inversion that limits the cell by altering the decrease in ambient temps, or by the internal limits of of the rising parcel of air. It may also be topped, and frequently is, by a change in the relative humidity.

In other words, the cell either peters out because it becomes thermally exhausted, or it's stopped by a change in the atmospheric lapse rate. The wind doesn't blow it over or cut it off, excepting the wind itself is sufficiently sheared in temperature or relative humidity.

The anvil represents blow-off from the top, and doesn't indicate cell movement. It indicates the direction of the shear at the top. The anvil points only in the direction of the wind at the top of the anvil.

Remember that a cell doesn't blow with the wind. Wind is constantly moving through a cell. The wind is moving faster than the cell is, and in different directions and diferent altitudes. The cell isn't a captive body air moving up and down, but but a body of moisturethrough which the wind blows. Where it's vertical development stops, the debris field moves with the wind at that level. In many cases, debris fields can be seen at other levels too,and may be seen to move in different directions.

In other words, the cell either peters out because it becomes thermally exhausted, or it's stopped by a change in the atmospheric lapse rate. The wind doesn't blow it over or cut it off, excepting the wind itself is sufficiently sheared in temperature or relative humidity.

The anvil represents blow-off from the top, and doesn't indicate cell movement. It indicates the direction of the shear at the top. The anvil points only in the direction of the wind at the top of the anvil.

Remember that a cell doesn't blow with the wind. Wind is constantly moving through a cell. The wind is moving faster than the cell is, and in different directions and diferent altitudes. The cell isn't a captive body air moving up and down, but but a body of moisturethrough which the wind blows. Where it's vertical development stops, the debris field moves with the wind at that level. In many cases, debris fields can be seen at other levels too,and may be seen to move in different directions.

Again, at that altitude, yes, that's where the shear axis is...or where the wind is blowning. But not necessarily any place else, nor does it indicate the direction of movement of the cell. Only the debris field at that altitude. Winds may be expected from different directions at different altitudes, and the storm movement may be in an entirely different direction.

Say Again Over

With you

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2005

- Posts

- 1,162

ksu_aviator

GO CATS

- Joined

- Dec 1, 2001

- Posts

- 1,327

With a few exceptions, (in the continental US) all frontal systems and thunderstorms move in a westerly direction. Winds aloft at altitudes where the anvil forms almost always run in a westerly direction. The sheer Avbug talks about is at the tropopause. That is where lapse rate, winds and pressure all change very dramatically.

So, as a thunderstorm builds to heights near the tropopause, the moisture that is carried up gets blown out to the west, forming the anvil. That is also the general direction of the movement of the storm. What to watch out for is the continuing build up beyond the anvil. That storm will have tremendous power and is likely to produce some hail and tornadic activity.

So, as a thunderstorm builds to heights near the tropopause, the moisture that is carried up gets blown out to the west, forming the anvil. That is also the general direction of the movement of the storm. What to watch out for is the continuing build up beyond the anvil. That storm will have tremendous power and is likely to produce some hail and tornadic activity.

On the grand scheme of things, cells move east. However, locally cells can move in any direction, including westbound.

Directly adjacent to the cell beneath the "overhang" or anvil isn't a good place to be, as storm products may be exhuasting there, however, the debris field by itself, with adequate distance from the storm, isn't dangerous by itself. Debris fields can extend hundreds of miles downrange, in some cases.

Directly adjacent to the cell beneath the "overhang" or anvil isn't a good place to be, as storm products may be exhuasting there, however, the debris field by itself, with adequate distance from the storm, isn't dangerous by itself. Debris fields can extend hundreds of miles downrange, in some cases.

regionalcap

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jan 27, 2002

- Posts

- 903

With a few exceptions, (in the continental US) all frontal systems and thunderstorms move in a westerly direction. Winds aloft at altitudes where the anvil forms almost always run in a westerly direction. The sheer Avbug talks about is at the tropopause. That is where lapse rate, winds and pressure all change very dramatically.

So, as a thunderstorm builds to heights near the tropopause, the moisture that is carried up gets blown out to the west, forming the anvil. That is also the general direction of the movement of the storm. What to watch out for is the continuing build up beyond the anvil. That storm will have tremendous power and is likely to produce some hail and tornadic activity.

Most systems and storms move easterly not westerly.

All I know is that it is not a good idea to fly through the overhang.

Through or under you meant to say.

With a few exceptions, (in the continental US) all frontal systems and thunderstorms move in a westerly direction. Winds aloft at altitudes where the anvil forms almost always run in a westerly direction.

Hmmm...I get the feeling that KSU_Aviator has either mis-spoken or he/she has never lived in the central plains during the January through December thunderstorm season.

Say Again Over

With you

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2005

- Posts

- 1,162

ksu_aviator

GO CATS

- Joined

- Dec 1, 2001

- Posts

- 1,327

Hmmm...I get the feeling that KSU_Aviator has either mis-spoken or he/she has never lived in the central plains during the January through December thunderstorm season.

Thus are the dangers of posting at 2am :nuts:

kansas

Seeee yaaaaaaaaa!

- Joined

- Mar 28, 2006

- Posts

- 125

On the grand scheme of things, cells move east. However, locally cells can move in any direction, including westbound.

Directly adjacent to the cell beneath the "overhang" or anvil isn't a good place to be, as storm products may be exhuasting there, however, the debris field by itself, with adequate distance from the storm, isn't dangerous by itself. Debris fields can extend hundreds of miles downrange, in some cases.

Believe it or not, the "overhang" isn't as bad as one would think. When things get nasty is when you get "donut-holed" in there, or have a nasty encounter with a gust front...or when you're next to something truly severe fountaining hail, but even that's not too common from my experience. Have spent quite a few hours flying right next to "the beast" in smooth air, again, depending on the position of the gust front.

Believe it or not, the "overhang" isn't as bad as one would think. When things get nasty is when you get "donut-holed" in there, or have a nasty encounter with a gust front...or when you're next to something truly severe fountaining hail, but even that's not too common from my experience. Have spent quite a few hours flying right next to "the beast" in smooth air, again, depending on the position of the gust front.

That's taking alot of risk if you ask me. It only takes once for it to be spitting out baseball size hail or worse for you do damage/destroy and airplane. As a general rule stay out from underneith the overhang.

regionalcap

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jan 27, 2002

- Posts

- 903

Believe it or not, the "overhang" isn't as bad as one would think. When things get nasty is when you get "donut-holed" in there, or have a nasty encounter with a gust front...or when you're next to something truly severe fountaining hail, but even that's not too common from my experience. Have spent quite a few hours flying right next to "the beast" in smooth air, again, depending on the position of the gust front.

You are giving bad advice. Stay away from the overhang. One day, if you keep it up, you will encounter bad hail. Just deviate away from the storm and be done with it.

cezzna

Remeber the analog

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2003

- Posts

- 291

The overhang is not so bad to fly as long as you're at leat 20 miles from the active part of the cell. Overhangs can be very long as avbug said extending for hundreds of miles. When cells start to train, the east side of convective acitvity is one big smeared overhang extending hundreds of miles.

As for cell movement, generally speaking on the surface they will move SW to NE but at the tropopause movement will be W to E. The trop can thermally cap a cell but when they really grow they can extend well into the stratosphere. Just think of the trop as a bad condom and a strong cell as a fratboy at the playboy mansion. You get the idea.

As for cell movement, generally speaking on the surface they will move SW to NE but at the tropopause movement will be W to E. The trop can thermally cap a cell but when they really grow they can extend well into the stratosphere. Just think of the trop as a bad condom and a strong cell as a fratboy at the playboy mansion. You get the idea.

kansas

Seeee yaaaaaaaaa!

- Joined

- Mar 28, 2006

- Posts

- 125

You are giving bad advice. Stay away from the overhang. One day, if you keep it up, you will encounter bad hail. Just deviate away from the storm and be done with it.

Well I'm by no means doing flight instruction/corporate/airline work in there. I was just passing along my personal experience from my weather modification days...and trust me, if you don't ever go under the overhang when doing weather mod, you will get NOTHING done.

While I'm at it, I might as well pass along some more non-scientific information on storm movement in the great plains. Seems to me (as well as a very experienced meteorologist that I know) that a lot of mid-summer storms tend to develop along/follow major highways. Perhaps this is a result of the heat rising from the asphalt?

Also, nearly all storms move in an easterly direction, more or less. However, many claim that if you ever encounter the rare westward-moving storm, you had better be prepared for some serious weather, including softball & volleyball size hail.

Just some personal experience stuff to think about.

Last edited:

Have spent quite a few hours flying right next to "the beast" in smooth air, again, depending on the position of the gust front.

Having spent quite a few hours flying right next to the "beast" in extremely rough, turbulent air...first of all, there is no "gust front," but a shear axis, and the debris field will be on the lee side of that; the downwind side.

If you were working above the base on weather mod, you were working the rising columns on the upshear, or upwind side, and there's certaily turbulence to be found there. Seeding the debris field is of no value.

In any event, there certainly exists hazard close to the thunderstorm, and certainly beneath the anvil, for some distance downwind.

kansas

Seeee yaaaaaaaaa!

- Joined

- Mar 28, 2006

- Posts

- 125

Having spent quite a few hours flying right next to the "beast" in extremely rough, turbulent air...first of all, there is no "gust front," but a shear axis, and the debris field will be on the lee side of that; the downwind side.

If you were working above the base on weather mod, you were working the rising columns on the upshear, or upwind side, and there's certaily turbulence to be found there. Seeding the debris field is of no value.

In any event, there certainly exists hazard close to the thunderstorm, and certainly beneath the anvil, for some distance downwind.

Well, we, as well as our meteorologist, called them gust fronts...sounds like a similar concept. I was working at the base, and although we had a Cheyenne that worked higher, I never got involved with that.

Yes, there's hazard close to the thunderstorm. Yes, I'm going to stay far away at my current job. But many of the notions people (and textbooks) have about thunderstorms are overblown, even though they may be true in a select few cases.

Say Again Over

With you

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2005

- Posts

- 1,162

Not quite sure what you mean by this statement, there are many pictures available of aircraft that were badly damaged, or worse from big wx systems, just recently in my area, the front of a Asiana A321 was destroyed. Not very healthy to under estimate this stuff, the books are an aid to understand the basics, those of us operating out there understand each system is different, there is no single way to look at each, remember the Chief Pilot at AA going into LIT, having nice shiny equipment is one thing, using your head is something else, flying over the top at 430 is not everyones option, what happens if you have to descend for some reason?Yes, there's hazard close to the thunderstorm. Yes, I'm going to stay far away at my current job. But many of the notions people (and textbooks) have about thunderstorms are overblown, even though they may be true in a select few cases

Yes, there's hazard close to the thunderstorm. Yes, I'm going to stay far away at my current job. But many of the notions people (and textbooks) have about thunderstorms are overblown, even though they may be true in a select few cases.

Having worked storms up close and personal from the base to the top with an airplane packed with scientists and ground support with some very sophisticated instrumentation on board and on the ground watching me...I can tell you it's every bit as bad as both the textbooks and real-life experiences say it is. If you never experienced it, don't mistake that lack of experience for reality.

Well, we, as well as our meteorologist, called them gust fronts...sounds like a similar concept. I was working at the base, and although we had a Cheyenne that worked higher, I never got involved with that.

A gust front occurs on the surface, and is the outer edge of outflow that accompanies a downdraft or microburst. It is the result of a descending column of air spreading out laterally as it's path is altered by terrain.

Aloft, there is no "gust front." You have wind direction, which as any student pilot knows, varies in intensity and direction at each level in the atmosphere. Wind blows from upwind to downwind, upshear to downshear. A debris field may exist downwind of the cell at any level, and several may exist moving in different directions. Further, while the "overhang" or "anvil" at the top of the storm marks blowoff at the thermal upper limit of the convective cell, it does not indicate the direction of movement of the cell. Only the wind direction at that altitude.

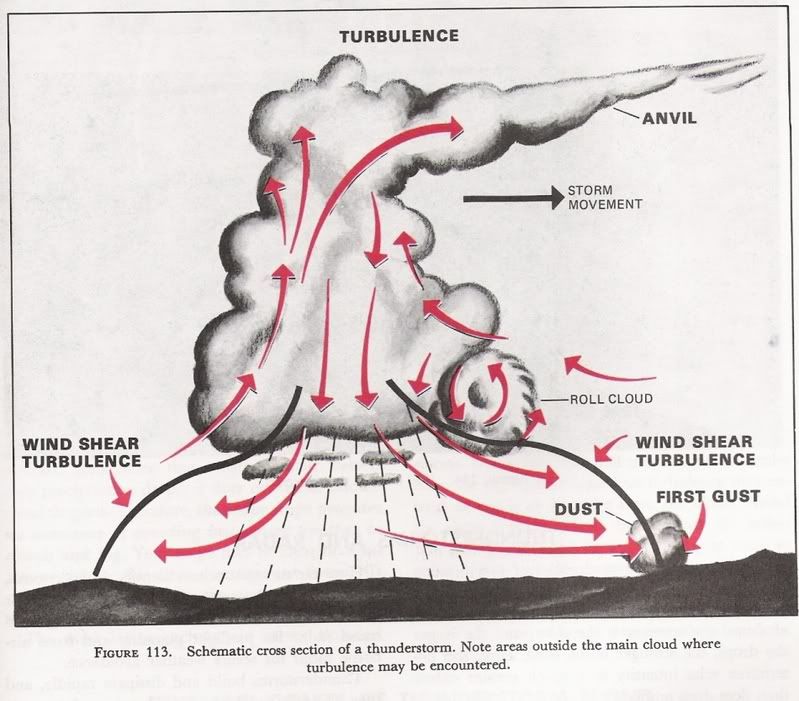

http://i94.photobucket.com/albums/l8...g?t=1176574474

This is from an aviation weather book produced by NOAA and FAA.

It shows movement in the direction of the anvil.

Yes, and no. There isn't a correlation between the two, though both are shown in the diagram. Further, the diagram shows air circulation vertically, but doesn't define horizontal flow through the cell, and is an oversimplification, and doesn't take into account variations in wind direction at various levels in the cell, or the continuous decay and fresh development that actually characterizes a convective cell.

The diagram isn't intended to suggest that a cell moves in the same direction as the anvil.

kansas

Seeee yaaaaaaaaa!

- Joined

- Mar 28, 2006

- Posts

- 125

Not quite sure what you mean by this statement, there are many pictures available of aircraft that were badly damaged, or worse from big wx systems, just recently in my area, the front of a Asiana A321 was destroyed. Not very healthy to under estimate this stuff, the books are an aid to understand the basics, those of us operating out there understand each system is different, there is no single way to look at each, remember the Chief Pilot at AA going into LIT, having nice shiny equipment is one thing, using your head is something else, flying over the top at 430 is not everyones option, what happens if you have to descend for some reason?

I'm not using my experiences as an excuse to violate regs, be unsafe, or to fly into something I shouldn't, even if I am pretty sure I would come out OK. Please, guys, I know the history behind all the crashes. ALL I AM DOING IS PASSING ALONG WHAT I LEARNED ABOUT STORMS FROM WEATHER MOD...not recommending that one should apply this knowledge to their current job, just general, "fun to know" thunderstorm knowledge. But perhaps I'll just keep my mouth shut next time.

av8orboy

LAS-FIDOE-MCY-SMOKY

- Joined

- Mar 14, 2004

- Posts

- 250

With a few exceptions, (in the continental US) all frontal systems and thunderstorms move in a westerly direction. Winds aloft at altitudes where the anvil forms almost always run in a westerly direction. The sheer Avbug talks about is at the tropopause. That is where lapse rate, winds and pressure all change very dramatically.

So, as a thunderstorm builds to heights near the tropopause, the moisture that is carried up gets blown out to the west, forming the anvil. That is also the general direction of the movement of the storm. What to watch out for is the continuing build up beyond the anvil. That storm will have tremendous power and is likely to produce some hail and tornadic activity.

Westerly? I guess KSU has a good meteorology program.

Say Again Over

With you

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2005

- Posts

- 1,162

snow-back

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jul 16, 2004

- Posts

- 329

2 more cents from an ex weather mod guy. It's probably been posted, but the anvil indicates what the direction the upper winds are blowing from. The steering winds for the storm are typically in the 700-500mB (15000'-18000') range...unless you start getting into the MCC (mesoscale convective complex) type storms.

There's also a difference between anvil and blowoff clouds. Anvils are still associated directly with the thunderstorm and can get nasty. Blowoff clouds can extend many miles downstream of a thunderstorm and are pretty tame. Also, those Mammatus clouds that look like big bubbles hanging down from a cell are NOT indicators of extreme turbulence. They are just slowy descending ice crystals.

AvBug, are still doing wx research?

There's also a difference between anvil and blowoff clouds. Anvils are still associated directly with the thunderstorm and can get nasty. Blowoff clouds can extend many miles downstream of a thunderstorm and are pretty tame. Also, those Mammatus clouds that look like big bubbles hanging down from a cell are NOT indicators of extreme turbulence. They are just slowy descending ice crystals.

AvBug, are still doing wx research?

Latest resources

-

-

-

-

-

AC 90-89C - Amateur-Built Aircraft and Ultralight Flight Testing HandbookAmateur-Built Aircraft and Ultralight Flight Testing Handbook

- Neal

- Updated: